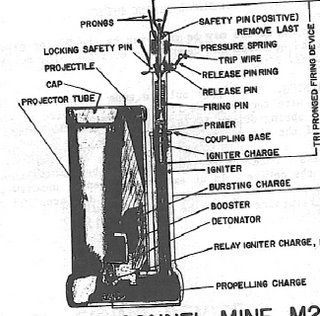

The picture shows a killer called the "Bouncing Betty" anti-personnel mine. When tripped, the mine bounces up at least chest high before exploding. The one who trips it will probably die or be maimed, but often in the great mystery of war, the one who trips it may survive while others die. This was the case around November of 1967 in the Street Without Joy in the I Corps of South Vietnam.

The picture shows a killer called the "Bouncing Betty" anti-personnel mine. When tripped, the mine bounces up at least chest high before exploding. The one who trips it will probably die or be maimed, but often in the great mystery of war, the one who trips it may survive while others die. This was the case around November of 1967 in the Street Without Joy in the I Corps of South Vietnam.My Marine battalion 1/3 was nearing the end of an operation. I was with H&S Company as part of an S-2 field interrogation unit. I usually had a tethered prisoner to push along in front of me while I followed in his footsteps. At times, we had tracked vehicles with us on flat ground. This was a bonus because I could walk in the trail left by the treads and not worry about tripping a mine. I didn't have either one on this day on the right flank, moving over hard bare ground. Real war isn't like the movies where troops bunch up and tell jokes or walk in a big cluster giving their opinions about life in general. The Marine Corps was strict on interval, at least fifteen paces between each man, because of things like the Bouncing Betty. If you bunched up, people died.

Something exploded up front. We froze. Word passed back that we were in a minefield. The officers were pissed because several grunts had bunched up. One tripped the mine, but the Marines behind him took the blast: one KIA and two wounded. (The KIA appeared untouched, but a pinhead piece of metal pierced his heart and he didn't even bleed. They had trouble finding the entry wound. His flak jacket was open or he would have probably survived.)

Walking through a minefield will age you. Everything, everyone, or every nightmare you have ever known flits through your mind. The Marine way behind me looked ready to puke. The one in front of me seemed miles away. This was a perfect place for an ambush, with a treeline on our right, slightly uphill. If they hit us, mines would help wipe us out. I wanted to sit and stay there. The ground was dry, cracked hard mud without footprints to follow. Staying there was not an option. I either lived or died, but I had to move forward and watch the ground for each step while checking the treeline for the ambush.

I cracked under the strain and ignored the treeline. An ambush was the least of my worries. That was the longest half hour I've ever spent in my life. It could have been longer, but I didn't have a watch and a combat scenario makes your mind alter time so you really don't know how much time has passed. I checked the ground, looking for imperfections or any sign the Marine in front had left where I knew I could safely step. I found nothing. I knew each step was my last as each foot put pressure on the soil. Sometimes, I closed my eyes just as I took a step and hesitated, waiting for the blast. When I finally cleared the field, I had much deeper appreciation for the little things like breathing or taking a step without fear of being blown up. Today, when I see bare ground with a treeline just beyond it, I'm right back in that minefield all over again.

Hey There. I found your blog using msn. This is an extremely well written article.

ReplyDeleteI'll be sure to bookmark it and come back to

read more of your useful info. Thanks for the post.

I'll certainly return.